Press release

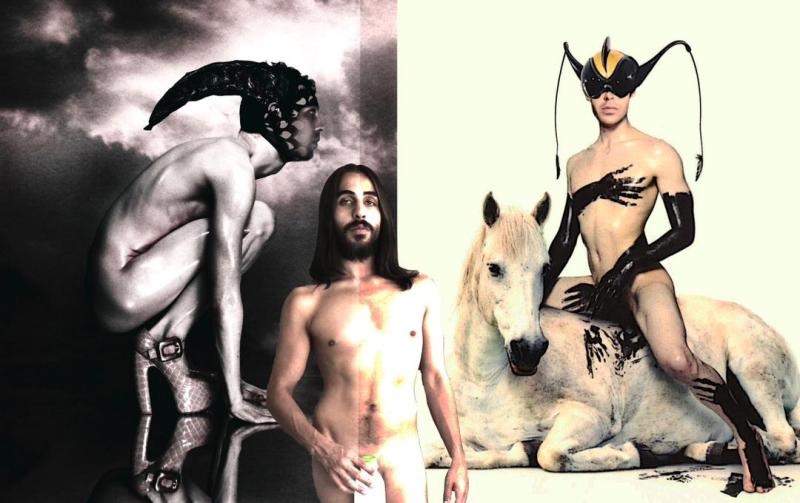

Salar Bil , Conceptual art , Surrealism , Dadaism forefather.

Salar Bil the forefather of Iran's conceptual fashion is the man who started conceptual fashion in Iran, Sophie Fontanel from france, Tim Blanks from Oceania, Diane Pernet from United States and Antonio Mancinelli from Italy four writers of fashion industry called him the progenitor of conceptual fashion, He is making his body of work from photography and video clips by his own hands to collages and digital works in a form of movie making with images, Salar Bil with his MISSION magazine is making a new wave about the century where images are spread at high speed like artificial intelligence, a background for the beginning of the metaverse has been established, on his instagram he explained about Surrealism on a video with his "cow collection"inspired by Gholam-Hossein Sa'edi up to today's Pop Artworks and imitations and appropriations which self-construction is rooted in the work of Duchamp, Salar Bil explained on his Instagram "The metaverse is the future of the internet or it's a video game or maybe it's a deeply uncomfortable, worse version of Zoom? It's hard to say. To a certain extent, talking about what "the metaverse" means is a bit like having a discussion about what "the internet" means in the 1970s." He explained about the subject that people can make avatars of themselves in the metaverse. Salar Bil's articles like Duchamp's have become popular in the western world, and they have been used for trends for the fashion companies that Christina Aguilera and Erykah Badu collaborate with specially from Iranian mood boards from Salar Bilehsavarchian.in his Salar Bil's journal he wrote : "Fashion is a complex cultural phenomenon made up of the creative design process of garments, cultural affiliation, commercial industry, and consumer needs. The processes of consumer adoption and the cycles of change in the fashion industry have traditionally mirrored each other. Fashion cycles refer to the organization of the fashion industry in seasons that is perpetuated by not only designers, producers, and retailers in Western contexts, but also more widely by institutions and organizations that partake in the mediation of new fashion through fashion weeks; fashion media including magazines, newspapers, and blogs; marketing activities including fashion film, modeling, PR; and stylist agencies as well as street culture, popular culture, and subcultures. Together, this forms a fashion system in the sense of an institutionalized set of processes that take an item of clothing or a style from creator to consumer (McCracken 1990; Davis 1994). This definition of the fashion system is broadened to include a more dialectical process between creator and consumer, allowing for the exchange between, for instance, street style and fashion industry. It also opens the system for conceptions of fashion that are not necessarily newly produced, such as vintage or fabric-based, similar to the corporeal fashion of beards. While these factors will appear throughout the examples and case studies, the main focus is on the social agenda at play when we as individuals engage with fashion. Fashioning identity is understood here as a science of appearance through not only dress and adornment, but also body management, including hair and makeup. It is about how we choose to look at a given time as part of staging who we are or who we would like others to think we are. Status display as a mix of reality and dream is treated as mainly a social and highly malleable quality that serves the paradoxical function of making us both fashionably unique and part of a crowd. This game of identity is organized in conceptions of novelty and symbolic meaning that, both in immaterial and material manifestations, are considered transitory. The focus on the cases become a vehicle for the main focus, namely, the mechanisms involved in fashioning identity. This approach is in line with social philosopher Gilles Lipovetsky who considers fashion to be a "specific form of social change, independent of any particular object" (1994: 16). The expression of our fashionable selves is played out in a series of brief, fictional moments in which past and future overlap. Fashion's favorite love interest is this ambiguity of the now. Within the context of fashioning identity, novelty is a tool for social distinction, a promise of transformation, or a shopping high while the business of fashion pushes the new to stimulate growth in the marketplace. As designer Christian Dior (2007: 7) wrote in his 1957 autobiography, the fashion industry is "a trade where novelty is all-important." So, what is considered new and desirable in fashion is promoted by the fashion industry and negotiated socially by consumers. This story of "hatless Jack" (Steinberg 2005) suggests a tension between the opposing principles of tradition and innovation that are never fully resolved. This causes a productive act of ambivalence, what sociologist Fred Davis called "ambivalence management" (1994: 25). The tensions this creates constitute a motor in the process of fashioning identity, and the intention is therefore not to eliminate these oppositions but to create conditions that will maintain them as a necessary part of the dynamic. The social exercise involved in fashioning identity relies on the nature of fashion literacy understood as the ability to decipher sartorial assemblages within the framework of shifting taste preferences. What is being read is the social currency. This is to be understood in the double meaning of what is considered current or modern within a specific context but also which currency or value will provide status. This is not necessarily afforded through conspicuous pecuniary means as has been the case historically, but increasingly operates through values or ideals signaling status locally negotiated and often ambivalent in expression. Clothes are no longer the badges of rank, profession, or trade as they were in preindustrial times (Wilson 2003: 242), but there are still politics of appearance. While means and access are relevant when studying this "status competition" (Davis 1994: 58), there has been a gradual move away from an emphasis on class. In response to the work on Simmel, Herbert Blumer (1969: 282) argued that fashion mechanisms were not a response to a need for class differentiation and emulation but were rooted in a wish to be in fashion, a process he termed "collective selection. Fashioning identity is partly about scrambling for attention not in a verbatim translation of visual expressions, but rather as a sartorial trick or "status ploy" (Davis 1994: 76) to be read by the fashion literate while deliberately misguiding those less versed in cracking dress codes. Fashioning identity is mainly a display of the public self the purpose of which is to communicate social belonging and individual distinction simultaneously. Fashion as a set of symbolic codes, as argued from Simmel (1957) to Susan Kaiser (2002), is suitable for this paradoxical endeavor that relies in part on shifting ideas of beauty, status, social standing, culture, sexuality, and gender. The sartorial dialectic is charged between the private core self and the fluctuating public self. But this mechanism has its limits. While fashion is a potent tool for the spectacle of identity, we are also so much more than how we manage our appearance. Fashioning identity is primarily a social game where the sartorial self is public and only in part an extension of the private self. In an attempt to explore the complex process of fashioning identity in the early twenty-first century, a range of examples and cases will be studied with ambivalence as a theme running through the article. The article as a whole may be seen as a form of reconsideration of Fred Davis's work in Fashion, Culture, and Identity, originally published in 1992. His observations are still relevant twentyfive years later, but the developments in society and the fashion industry call for an update to match the current context. Davis's key concepts will be reexamined through a series of examples and cases, each section representing a different take on the theme of status tactics. Davis approached social identity as unstable and contradictory, individually negotiated and communally shared. This turbulent process is in part fueled by fashion. A central quote for the article concerns the continuous tension from which fashioning identity gains its strength: The sartorial dialectic of status assumes many voices, each somewhat differently toned from the other but all seeking, however unwittingly, to register a fitting representation of self, be it by overplaying status signals, underplaying them, or mixing them in such a fashion as to intrigue or confound one's company. (Davis 1994: 63) For Davis, social identity is more than symbols of social class or status but include any aspect of self that individuals use to communicate symbolically with others. In relation to fashion, this includes primarily nondiscursive visual and tactile means of representation within a social, cultural, and economic context. This definition is elastic, and the focus will mainly be on what Davis (1994: 26-27) refers to as "master statuses" from the point of view that ambivalence is a way of enacting gender roles, social class identification, age, and sexuality through fashion that is hardwired to challenge the fixed and settled, creating shifts in perceptions of beauty, ideals, and status in the process. Fashion's appetite for change has been criticized for promoting an image of women as objects, for maintaining class structures, and for obstructing sustainability. The apparent pointlessness of fashion change has also invited satire, for instance, by Oscar Wilde in 1887: "Fashion is a form of ugliness so intolerable that we have to alter it every six months" (2004: 39). Though phrased for the express purpose of humor, this unreliability of fashion in terms of, for instance, shifting conceptions of beauty points to fashioning identity as schizophrenic. Social identity displays are highly personal. We have selected them, they cover our bodies, and in the capacity of a second skin, we transfer our warmth and scent to these fashionable surfaces. But they also function as social messages of self- and group belonging. The friction between individuality and community as conferred in a continuous visual and symbolic development is rooted in Simmel's seminal observations originally published in 1904. He argued that the transformative structure in fashion comes through the social tension between distinction and imitation-what he termed the social regulation through "aesthetic judgment" (Simmel 1957: 545)-in which the symbolic demonstration of status is copied in a linear adoption process. This progression moves toward an inevitable point of saturation that reboots the system. In this sense, fashioning identity is a tragic game, a time bomb hardwired to self-detonate as the inevitable part of diffusion and social saturation. Though he refined the concept, Simmel's observations were not entirely new. In 1818, art critic William Hazlitt described fashion as "an odd jumble of contradictions, of sympathies and antipathies. It exists only by its being participated among a certain number of persons, and its essence is destroyed by being communicated to a greater number". While these contradictions form the basis in the present treatment of fashioning identity, the notion of death by popularity will also be challenged when looking at the perseverance of some trends such as leopard print, just as the dogma of distinction will be explored through its inversion, namely, looking fashionably bland. The social schizophrenia of fashion runs on taste, access, and the "artful manipulation" (Davis 1994: 17) of the fashion industry. In early twenty-first century, the inner workings of fashioning identity are still informed by the pulse of the fashion industry that to a certain extent controls supply and thereby the tools for engaging in the social game of fashion. However, the premise of this aesthetic judgment has shifted over time in line with changes in the industry, society, and social norms. The historical perspective is included here to provide background to the mechanisms of status competition in contemporary fashion. As with many other sides of Kennedy's life, his choice of what to wear on his head has been subject to speculation in terms of social, economic, technological, and personal developments. Hat sales had been on the down since the 1950s, and Kennedy may have brought the development to its culmination. But there were also other perspectives. Was the rise of the hatless man a reflection of the flourishing youth culture? Was it caused by the increase in cars that left less room for a hat than in a tram or bus? Or can Kennedy's giving up hats be explained simply by him wanting to show off a gorgeous head of hair? From a fashion perspective, Kennedy was a trendsetter because of his social standing, his powerful position, and for what has been described as his "Cool Factor" (Betts 2007). He was navigating an era of transition and, in a very minor way, his ambivalence toward hats might be seen to reflect this. As a trendsetter, he was instrumental in the diffusion of the trend for going hatless while also emulating the current mood. In this sense, Kennedy's sartorial choices can be read as fashion flows. Fashion flows are understood here as the consumer adoption of new styles in fashion. This social dynamic is informed by the fashion industry, culture, and societal contexts. Fashion flows-sometimes also referred to as tricklemovements-rest on the paradoxical need among especially the socially mobile for both individual distinction and group identification. The adoption process is often triggered by trendsetters and driven forward through sartorial copying for the purpose of connection with fluctuating definitions of status. The element of delay or time lag between the fashion forward and the fashion tardy is central in achieving the effect of distinction. Being fashionably on time has become much easier with industrialized production and globalized consumption of fashion, and as a consequence achieving and maintaining distinction have become equally difficult. This has caused the fashionably inclined to reconsider methods of distinction that are more demonstratively ambiguous than Kennedy's deliberations over a top hat as a way of maintaining distinction longer. But rather than representing fashion mutiny through dismantling the hierarchy of fashion, these new strategies may be seen as a rediscovery of what fashion is and can be within a social context. The following text outlines the development of key terms with regard to fashion flows within a historical framework to provide a theoretical context of how the social mechanisms of distinction have been adjusted over time. The brief description of these fashion flows constitute the conditions for fashioning identity as something consumers chose to either engage with or keep away from. The development of ambiguous social currency relies on a partial dismissal of James Laver's (1899-1975) early description of fashion, namely, as "the dress of idleness and pleasure" (Laver 1946: 114). This approach saw fashion as an indulgence for the privileged few. In the fashion industry, the production of luxury was given more structure with the rise of haute couture that is often credited to Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895) who founded House of Worth in 1858 in Paris. With Worth and haute couture, fashion was loosely organized in biannual seasons forming a fashion cycle that accommodated the process of distinction and imitation later described by Simmel. This created a vertical flow according to which the higher classes were copied by the lower motivated by status aspirations. The hierarchy of price and prestige characterized the period in fashion history from 1850 to 1950 where the main focus was on handmade couture and industrially produced copies of couture that created a vertical dynamic between the social layers of society. Much of the early work on fashion as a social practice emphasized class and wealth as the primary agents of status claims. The development of ambiguous social currency relies on a partial dismissal of James Laver's (1899-1975) early description of fashion, namely, as "the dress of idleness and pleasure" (Laver 1946: 114). This approach saw fashion as an indulgence for the privileged few. In the fashion industry, the production of luxury was given more structure with the rise of haute couture that is often credited to Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895) who founded House of Worth in 1858 in Paris. With Worth and haute couture, fashion was loosely organized in biannual seasons forming a fashion cycle that accommodated the process of distinction and imitation later described by Simmel. This created a vertical flow according to which the higher classes were copied by the lower motivated by status aspirations. The hierarchy of price and prestige characterized the period in fashion history from 1850 to 1950 where the main focus was on handmade couture and industrially produced copies of couture that created a vertical dynamic between the social layers of society. Much of the early work on fashion as a social practice emphasized class and wealth as the primary agents of status claims. Fashion worked as a vehicle of conveying status aspirations and social affiliations through symbolic meaning but also material value. Already from the beginning of twentieth century, there were signs of a gradual democratization understood as a development from wealthy women being the fashion leaders toward a premise where material luxury was not necessarily the only imaginable form of social currency. This process was promoted by the development in garment production that made the copies cheaper, quicker to make, and available to a wider group of consumers. In the twenty-first century, men are not obliged to wear powdered wigs and women have been freed from the cages of the crinolines and corsets. Individuality and freedom are admired values that can be communicated through the way we chose to look. However, fashion still runs on the social power structures, and conspicuous consumption is still in operation. The vertical flow in Kennedy's checking his hat, so to speak, that was seen to spread to the masses is at a structural level similar to the frenzy of getting your feet in a pair of musician Kanye West YEEZY Adidas sneakers (2015) that will make some people camp outside a store for days. Exclusivity either through price or access is still at play, with celebrities in the lead, including actors and singers but also stylists, fashion editors, and bloggers. In this hyper-visual age, celebrities have come closer to their fans through social media and in limited edition capsule collections with fast fashion increasing their power and maintaining the vertical flow of fashion. In 1961, the mood was young and liberated in the Western world. Fashion flirted with freedom of mind and body rejecting what was perceived as the restrictions and stuffiness of older generations. Youth became the prime social currency in fashion that as a consequence was considered to follow a horizontal flow. In a critique of the vertical flow theory, Charles W. King argued that fashion as "social contagion" (1963) moves across socioeconomic groups simultaneously in a market where consumers have the freedom to choose from all styles. Rather than the economic elite playing the key role in directing fashion adoption, it was the influentials who inspired change not vertically across strata but horizontally within specific social affiliations: "Personal transmission of fashion information moves primarily horizontally rather than vertically in the class hierarchy" (King 1963: 112). King was foresighted in suggesting his idea of "simultaneous adoption" well before the digital mediation of fashion information, the rise of everyman as fashion leader-from blogger to celebrity designer-and the revolution in style, price, and availability of fast fashion. The postwar licensing practice of designers contributed to paving the way for this development by pushing fashion in a democratic direction in the form of ready-to-wear, which was already on the rise in the United States. The development toward a more mutual dialogue between the dresser and dressed was gradual. Christian Dior (1905-1957) was one of the first designers who understood how to take advantage of the rise of consumer culture that came in the wake of World War II. He made lucrative licensing deals for parts of his collections and lines of side products such as makeup, stockings, and bijouterie for especially the American market that was booming at the time. Licensing was good for business and an effective way to spread the brand Dior. Exclusivity as both a product and experience was opened to the masses because more people had access to the haute couture brand Dior if not the actual haute couture. Although licensing was an accepted and institutionalized practice, copying was difficult to control, and despite the fact that, for instance, Christian Dior released mass-produced retail collections, copies of his creations were often in department stores before the couture customers got their hands on the original. This was a step in the direction of reorganizing and perhaps ultimately dismantling the hierarchy of fashion where traditionally only members of the social elite were in a position to both influence and pursue status play through fashion. Ready-to-wear became an important factor in the changed relationship between production and practice, away from the designer as auteur and toward the designer as interpreter of street and youth culture. As opposed to the couture designers who produced ready-to-wear as a subline, a new generation of designers such as Mary Quant and André Courrèges beginning in the late 1950s made only ready-to-wear. Mary Quant and André Courrèges were ambassadors of the horizontal flow in fashion where the trendsetters were not necessarily the social elite. These designers contributed to making standard sizes in fashionable clothing more widespread and also worked toward dissolving the boundaries between casual and evening wear according to the philosophy that modern women did not have time to change out of their work clothes before going out at night. Their fashion ambitions were more democratic in their attempt to make fashionable clothes available to women regardless of economic status. This vision was reflected in the price as well as design and functionality of the clothes. As Quant puts it in her autobiography: "There was a time when clothes were a sure sign of a woman's social position and income group. But now, snobbery has gone out of fashion, and in our shops you will find duchesses jostling with typists to buy the same dress" (Quant 1966: 75). This approach to fashion testifies to the step that took place in the 1960s from hemline to attitude that Elizabeth Wilson has described as the "snobbery of uniqueness" (2003: 193). The same year as Kennedy's Inauguration, the aptly named shift-dress materialized the attitude of the time. The sleeveless dress with straight lines and minimal detailing allowed for freedom of movement suitable for the growing youth culture. As a visual expression, the shift was a paraphrase of the 1920s flapper dress as well as of the 1957 Balenciaga Sack-dress. The loose shift dress, also known as "The Little Nothing"-dress, was heralded for its uncluttered look for those who were wealthy enough to demonstrate that they did not have to put in too much effort: "who hate to seem as though they've tried too hard". In 1961, the conspicuously blasé look flowed from the youth culture of the streets to the silver screen, with Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany's in the elegant black Givenchy dress and to Jackie Kennedy as she moved with her husband into the White House. The vertical flow was seen in how these celebrities popularized the pared-down look, but they were diffusing a horizontal flow that originated with the young and the restless. The suggestion is that various flows coexist and even feed off each other, which already in 1961 indicates the complexity of fashioning identity. The example also indicates a development where the wealthy are not automatically the trendsetters, and that high status is often displayed discretely as a form of inconspicuous ostentation. The shift dress, then, communicated the horizontal flow of youth culture while also displaying a vertical flow, because the high-end designer dress was still a luxury item that only the elite had access to. Before the upward fashion flow was associated with subcultures, it was linked to the styles that were soaked up from the lower classes. Referring to the 1960s, George Field (1970) argued that "white collar" imitated "blue collar" lifestyle and clothing preferences, with examples such as camping, pickup trucks, and bowling. In fashion, he discussed the "upward flow" of denim jeans. From a background as work wear, its rise to fashion icon took off in the 1950s, when jeans became a symbol of resistance to conformity worn by young dissidents personified by James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955; directed by Nicholas Ray; Warner Bros). As jeans flowed upward in the 1950s, they revealed their accommodating potential appealing to the young trendsetters as well as a wide range of social groups, including hippies and bikers and, later, heavy metal, punk, hip-hop, and grunge. Since the 1970s, jeans have transcended gender, age, social status, and cultural boundaries, becoming part of a global fashion uniform. With the introduction of designer jeans in the 1970s and the first denim haute couture gown by Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel AW 2006 collection, denim can be seen to represent a more general leveling of the fashion hierarchy where distinction within this limited example appears through subtler means such as adjustments in wash, cut, brand, and assemblage of the jeans rather than radically different styles introduced seasonally. The ambivalence of fashioning identity exemplified with the Kennedy inauguration has only increased with the democratization of style brought on by mass-fashion and digital media. The 1990s saw the rise of fast fashion characterized by more rapid and cheaper production than ready-to-wear By outsourcing the production to low-cost areas such as the Far East, mass-fashion retail chains have been able to produce fashion inspired by both runway fashion and street-style at a pace and a price point that have altered the conditions for the fashion cycle toward a greater degree of leveling between high and mass fashion.

A cycle has traditionally begun with a new season and lasted until the next season so the process could start over. With fast fashion and digital media, this cadence has become more of a continuous influx when companies such as H&M and Zara can go from idea to store shelf in under two weeks and offer thousands of new products a year. The biannual fashion cycle still provides the industry and media with a certain rhythm and sense of anticipation most markedly with fashion weeks, but the consumers are not necessarily stepping to the beat. To accommodate this, the fashion brands have added mid-season lines to their assortment, pushing the fashion industry at all levels toward what Anna Wintour, editor-inchief of American Vogue, has termed "a seasonless cycle" (Thomas 2007: 316). If not exactly dismantling the fashion cycle, the development has posed a challenge to the traditional fashion hierarchy of price, accessibility, and quality. An example of this radical shift in the culture of fashion is the luxury fast fashion of high-low capsule collections set off by H&M with Karl Lagerfeld in 2004, followed by, among others, Stella McCartney, Viktor & Rolf, Comme des Garçons, Lanvin, and Maison Margiela. Rather than losing its novelty value, these collaborations have only increased in popularity in their more than a decade of existence. The "Balmain x H&M" in 2015 created intense interest in many of the selected cities where the collection was released. Customers slept outside the stores for days in order to get their hands on the coveted items, demonstrating new systems of anticipation beyond the traditional luxury system. Many of the styles were bought for the explicit purpose of resale, some of them selling for three times the original price on eBay the same day they were sold in stores. This demonstrates the complication of the fashion hierarchy and direction of fashion flows when a high street version of luxury approaches the price of a "real" Balmain. In a qualitative study of how H&M uses co-branding as a strategy, Anne Peirson-Smith (2014: 58) argues that the cohabitation of high and low brands, as seen in these capsule collections, are intended to "establish brand visibility and credibility amongst aspirational consumers."Crossovers are not just seen between luxury and mass fashion but also between brands such as Liberty of London x Acne Studios (2014), between creative fields such as artist Damien Hirst for Levi's (2008), filmmaker David Lynch for footwear designer Christian Louboutin (2007), and celebrity collaborations such as Kate Moss for Topshop (since 2007). And not all brand partnerships are one-offs, some being ongoing, such as Yohji Yamamoto's line Y-3 for Adidas. A related development in designer collaborations is the high-high projects between luxury brands or designers. An example is Karl Lagerfeld x Louis Vuitton (2014) that was part of the limited edition series of accessories that celebrated the iconic LV-monogram in honor of the house's 160th anniversary. Though this is not the first time Louis Vuitton has invited other designers to reinterpret their monogram, the example is still interesting in relation to how this type of collaboration seems to challenge the argument that high-low collaborations are a success because they attract new consumer segments to both brands (Fury 2014). Because both Louis Vuitton and Karl Lagerfeld as creative director of Chanel represent luxury fashion, they therefore have similar target groups. However, the collaboration still communicates a positive message of mutual creative honoring which reflects the positive outcome of the high-low capsule collections. The projected leveling of the fashion hierarchy and the reduction of time lag between inception and demise have created conditions for a scattered flow in the adoption process that moves in several directions at once. This tendency has been enhanced by the general democratic development in which anyone can potentially be a designer, fashion editor, and style icon (Thomas 2007; Agins 1999; Lipovetsky 1994). The effects of this have been understood as an acceleration of fashion (Loschek 2009), stylistic pluralism (Laver 2012), and creative democracy (Polhemus 1994). Fashioning identity requires ambivalence management within shifting social, aesthetic, and symbolic regulations. While it still holds true more than a century later that "change itself does not change" (Simmel 1957: 545), the fashion flows have become more complex. The more difficult conditions for distinction have promoted unscrupulous visual hijacking and mannered protests in fashion for the sole purpose of scrambling the signals of social belonging. Obscuring the sartorial symbols enhances the element of resistance in fashion, stimulating the dynamic where some are early to accept novelties in fashion while others need a longer gestation period. Fashioning identity is personal, intimately linked as it is to our bodies, social bonds, and cultural ties. We tell stories with the way we choose to look, mixing fact and fiction for the desired social effect. Fashion narratives are key vehicles in transmitting these shifting messages of identity. Engaging in identity politics through fashion has become more democratized across gender, class status, ethnic, and age gaps, bound closer through digital media and fast fashion. If we consider fashion to be a powerful potion, the concentration is individually chosen depending on life situation and personal preference. Fashioning identity, regardless of the degree of engagement, operates with a symbolic content that is the same regardless of the concentration. This is linked to the social standards of looking the part in contemporary fashion that allow for schizophrenic shifts between fashionable personas-punks one day, ballerina the next-without it being either more or less than playful self-curation."

Street 2047 34 Ave SW

City/Town Calgary

State/Province/Region Alberta

Zip/Postal Code T2T 2C4

Phone Number (403) 242-4040

Country Canada

Publisher of global fashion news

This release was published on openPR.

Permanent link to this press release:

Copy

Please set a link in the press area of your homepage to this press release on openPR. openPR disclaims liability for any content contained in this release.

You can edit or delete your press release Salar Bil , Conceptual art , Surrealism , Dadaism forefather. here

News-ID: 3136387 • Views: …

More Releases for Davis

Attorney Michael J. Davis Joins Lyda Law Firm

Lyda Law Firm has announced the addition of Michael J. Davis, Of Counsel to the growing firm. Davis brings with him over 30 years of legal experience and a wealth of knowledge related to business law, commercial litigation, and debt resolution.

Prior to joining Lyda Law Firm, Davis was a partner with DLG Law Group LLC and Archer Bay PA in Denver, and Springer Brown Covey Gaertner and Davis in Chicago,…

Global Forged Steel Globe Valves Market Research Report 2018-2025 | Global Key …

This research report titled “Global Forged Steel Globe Valves Market” Insights, Forecast to 2025 has been added to the wide online database managed by Market Research Hub (MRH). The study discusses the prime market growth factors along with future projections expected to impact the Forged Steel Globe Valves Market during the period between 2018 and 2025. The concerned sector is analyzed based on different market factors including drivers, restraints and…

Global Plastics Processing Machinery Market 2018 : Attractiveness, Analysis and …

Researchmoz added Most up-to-date research on "Global Plastics Processing Machinery Sales Market Report 2018" to its huge collection of research reports.

This report studies the global Plastics Processing Machinery market status and forecast, categorizes the global Plastics Processing Machinery market size (value & volume) by key players, type, application, and region. This report focuses on the top players in North America, Europe, China, Japan, Southeast Asia India and Other regions (Middle…

Global Automatic Knife Gate Valves Market Forecast 2018-2025 Davis Valve, Weir, …

Recently added detailed market study "Global Automatic Knife Gate Valves Market" examines the performance of the Automatic Knife Gate Valves market 2018. It encloses an in-depth Research of the Automatic Knife Gate Valves market state and the competitive landscape globally. This report analyzes the potential of Automatic Knife Gate Valves market in the present and the future prospects from various angles in detail.

The Global Automatic Knife Gate Valves Market 2018…

Hart Davis Hart Wine Auction 2017-10-06

Watch you cellars, new wine values from Hart Davis Hart Wine Auction long trading day

The auction room at Hart Davis Hart Wine Auction was carefully prepared, the bidders flooded into the auction room, after the wine tasting was finished. There were more then 508 lots offered and the wine auction closed with some remarkably results.

The largest portion of the complete range at the wine trading day, got wines from wine…

Global Synthetic Resin Teeth Market 2017 by Key Players: Ruthinium, Davis Schott …

This report on global Synthetic Resin Teeth market precisely studies the various aspects of Synthetic Resin Teeth industry.At Forefront the report proffers prudent insights into the trends in Synthetic Resin Teeth market along with the market dimensions and forecast for the duration 2016 to 2022.Along with this,research study on Synthetic Resin Teeth market also integrates detailed analysis of various market segments on the basis of product type, applications and geography.

Further…